Top 2025 Fossil Discoveries

2025 was a spectacular year for paleontology! Dinosaur skin color patterning, groundbreaking news about the Nanotyrannus vs young T. rex debate that shook the paleontology community, ancient ecosystems bouncing back after devastating mass extinctions… The discoveries released this year seemed almost endless.

What you’ll read here are some of the most exciting studies published this year, and this was just scratching the surface. There were so many new discoveries that each deserve their own spotlight, but alas, we can only fit a few. So let’s go with some Elevation Science favorites!

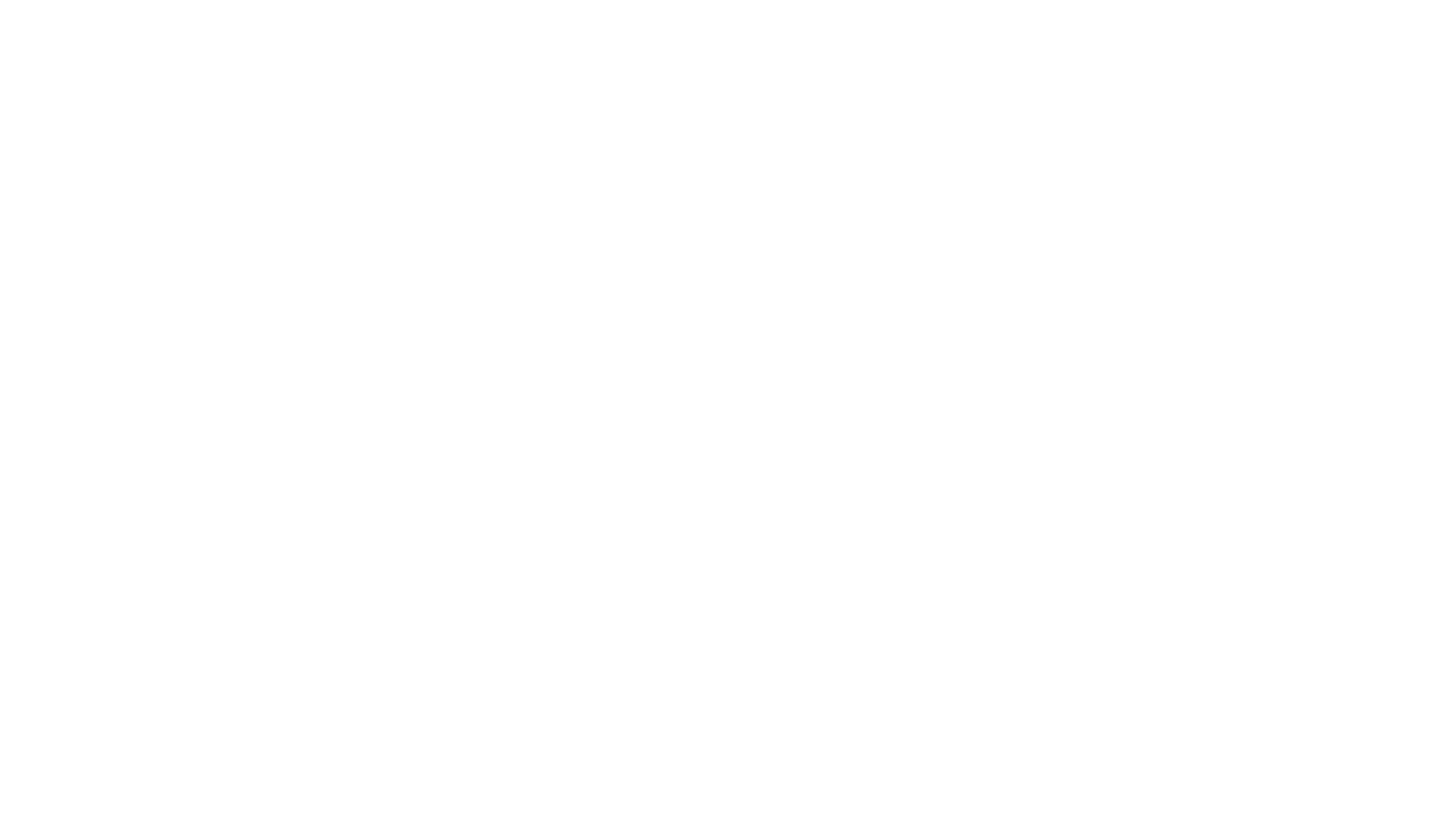

Diplodocus Skin Reveals the First Evidence of Color Patterning in Sauropods

Fossil skin from juvenile Diplodocus, discovered at the famous Mother’s Day site excavated by Elevation Science, preserved microscopic structures called melanosomes, a major milestone because melanosomes are linked to coloration in living animals (such as birds). The team examined preserved scales from several juvenile Diplodocus skin samples and identified two melanosome shapes, which can correspond to different pigment types. This suggests sauropods may have had patterned or speckled skin, and that pigment reconstruction isn’t limited to feathered dinosaurs. This study pushes dinosaur appearance science forward in a big way, helping us move beyond “gray giant” stereotypes and giving new life to how we reconstruct sauropods.

Nanotyrannus Confirmed as a Distinct Species (Not a Juvenile T. rex)

Not one, but two studies in 2025 strengthened the case that Nanotyrannus was a distinct species, not just a teenage T. rex. Researchers studied the hyoid (throat) bone from the Nanotyrannus holotype skull and counted growth rings, showing that the animal was ~15–18 years old and likely mature. The skull belonged to an animal that wasn’t a juvenile, supporting the interpretation that multiple tyrannosaur species shared the ecosystem. If Nanotyrannus was real, then juvenile T. rex didn’t “fill the niche” of smaller predators, meaning Late Cretaceous ecosystems were more diverse and competitive than we originally assumed.

Thousands of Triassic Dinosaur Footprints Discovered in the Italian Alps

A wildlife photographer stumbled upon one of Europe’s largest collections of dinosaur tracks: an estimated 20,000 footprints, dating to about 210 million years ago. The footprints are clearly preserved in Alpine rock faces and include trackways from large herbivorous dinosaurs resembling early prosauropods (Plateosaurus-like animals). Some footprint arrangements suggest group movement, with individuals walking at steady paces, a glimpse of herd behavior from the Late Triassic. Tracksites like this reveal real animal behavior and movement patterns that bones can’t. Sometimes, the best fossils are found completely by accident!

Major New Footprints Unearthed on Britain’s “Dinosaur Highway”

A team of researchers returned to Oxfordshire’s famous tracksite and uncovered hundreds more footprints, including evidence of Europe’s longest sauropod trackway. The site preserves multiple trackways, some more than 150 meters long (~492 feet), created by large herbivorous sauropods and a large carnivore (Megalosaurus-like). The variety and overlap of tracks suggest multiple dinosaurs used the same landscape repeatedly, possibly at different times, and that the area was likely a muddy, lagoon-like habitat. This is some of the clearest evidence of dinosaur behavior in Britain, showing movement across an ecosystem.

A New Duck-Billed Dinosaur Named from New Mexico: Ahshiselsaurus wimani

In 2025, scientists formally named Ahshiselsaurus wimani, a new large plant-eating dinosaur based on fossil material long held in museum collections. The dinosaur was identified using anatomical features preserved in bones, demonstrating how re-examining “known” fossils can produce major discoveries. The discovery expands our understanding of dinosaur diversity in Late Cretaceous North America and highlights the value of museum collections as scientific libraries. Paleontology doesn’t just happen out in the field; some of the most important discoveries come from specimens already in storage!

A Stunning Archaeopteryx Study Clarifies Early Bird Flight

A 2025 study of the famous “Chicago Archaeopteryx” provided new insight into how early birds may have flown and what they could do in the air. Scientists analyzed the fossil’s anatomy in fine detail, including bones and feather-related structures, to interpret its flight ability. The study adds data to a major evolutionary question: how flight evolved from dinosaur ancestors and what early birds were capable of. Archaeopteryx remains one of the most famous “transitional fossils” in science and new research keeps refining the evolution of one of nature’s greatest innovations: powered flight.

183-Million-Year-Old Plesiosaur Preserved with Soft Tissue and Skin

A Jurassic plesiosaur fossil, Plesiopterys wildi, was found with rare preserved soft tissue and skin; including skin outlines and texture. Soft tissue can reveal movement adaptations, body shape, and potential lifestyle traits not visible in skeletons. Exceptional preservation is one of the best ways to “bring fossils back to life,” improving our reconstructions and helping us understand how ancient animals functioned.

An Arctic Marine Bonebed Reveals Rapid Recovery After the End-Permian Extinction

A bonebed in the Arctic preserved a marine ecosystem from roughly 249 million years ago, soon after Earth’s most devastating mass extinction. Fossils of marine animals preserved together show an ecosystem rebuilding after the catastrophe. However, recovery may have been faster and more complex than expected, suggesting some ecosystems rebound sooner under the right conditions. Understanding past mass extinction recovery can inform how ecosystems respond to today’s biodiversity crises.

First South American Amber with Insects Discovered in Ecuador

For the first time, amber from South America was confirmed to contain insect inclusions! Amber preserves insects, plant fragments, and other tiny organisms in amazing detail, often with microscopic structures intact. This discovery expands what we know about ancient ecosystems in Gondwana and provides a new fossil record source for tropical biodiversity. Amber fossils are fantastic time capsules; finding them in new regions helps fill in huge geographic gaps in our understanding of the fossil record.

North America’s Oldest Known Pterosaur Found in Arizona

A Triassic pterosaur fossil, Eotephradactylus mcintireae, pushes back North America’s pterosaur record, helping map the early evolution of these flying reptiles. Fossil remains were compared against already-known pterosaur anatomy to confirm identification and age. Pterosaurs were already spreading widely across Pangea early in their history, and North America’s record is more ancient than previously confirmed. Early pterosaur fossils are rare, so each new find helps reconstruct the early phases of flight evolution among reptiles.

A New Thai Pterosaur Named: Garudapterus buffetauti

A new pterosaur species described in Thailand expands the known diversity and distribution of ancient flying reptiles. Fossils preserve diagnostic anatomical traits that allow scientists to assign the specimen to a specific group and identify it as distinct. Pterosaurs were more widespread in Southeast Asia than the fossil record previously suggested, and the region continues to yield important new species.

Penguin Fossils Help Rewrite the Story of Penguin Evolution

New fossil evidence refined the tale of how penguins diversified early in their evolutionary history. Fossils preserve skeletal features that can be compared across penguin species and mapped onto evolutionary trees. Penguins were diversifying and adapting earlier than we once assumed, supporting a richer evolutionary history in the Southern Hemisphere. Fossils show exactly how they became the specialized swimmers we know today, and how climate and oceans shaped them.

A Giant Ancient Shark Ruled the Seas Before Megalodon

Yep, you read that right, shark fans. A 2025 study highlighted evidence of a massive ancient shark that lived long before Megalodon, giving us a new “giant predator”. Vertebrae-based fossil material helped estimate size and ecology beyond what the teeth alone can reveal. Shark gigantism evolved multiple times, and ancient oceans hosted major predators long before the species most people know and love. It shows how marine ecosystems have supported enormous predators repeatedly in Earth’s history, and that Megalodon was never the only giant shark on the radar.

A Fish Fossil Preserves Stomach Contents and Possible Color Pattern

A Miocene fish fossil preserved both stomach contents and pigment-related features. Fossils preserved internal material and surface structures that allowed scientists to infer diet and coloration. Fossils like this can capture behavior and ecology (what an animal ate, and sometimes, how it looked) when preservation conditions are just right. These fossils help reconstruct ancient food webs.

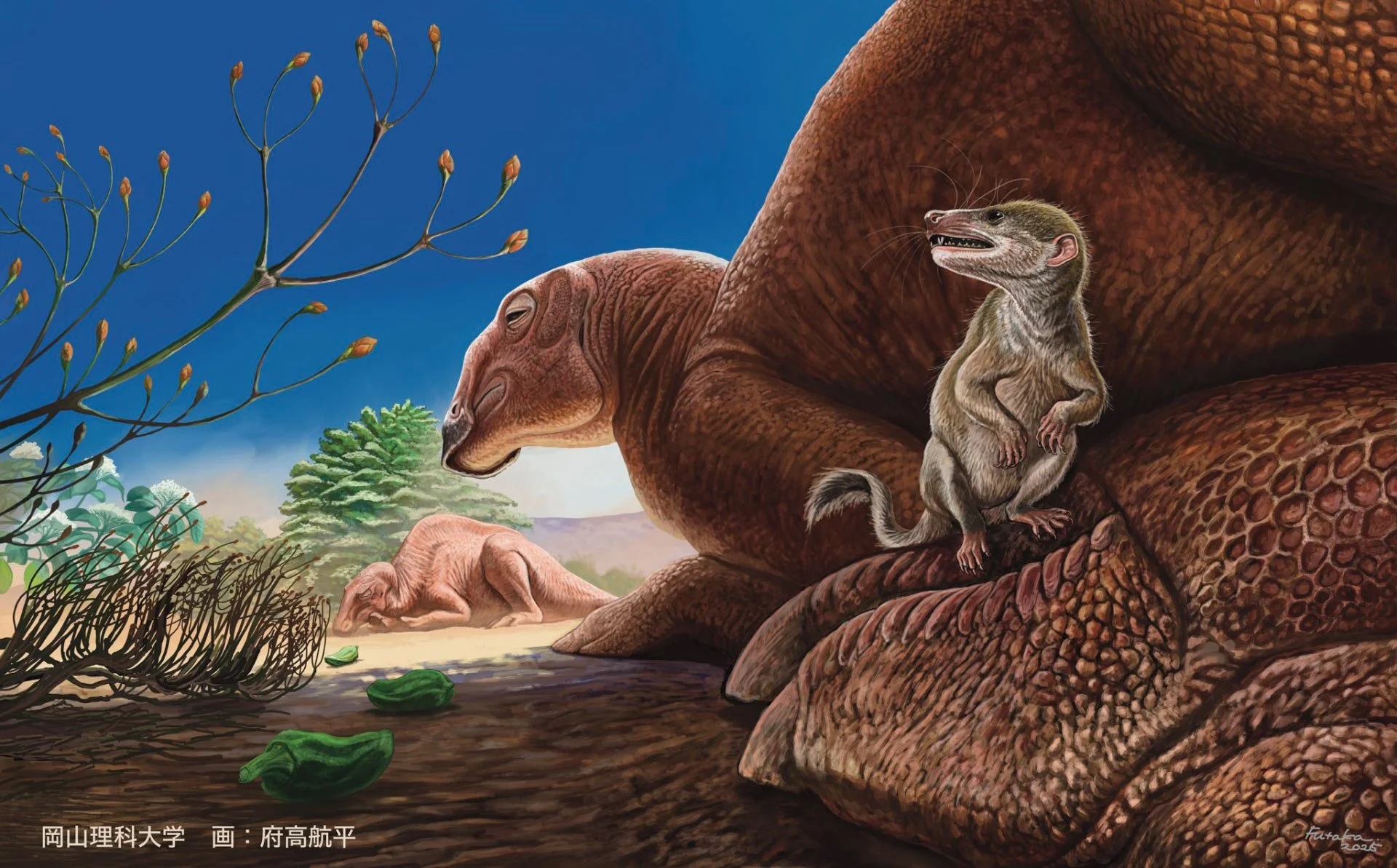

A New Cretaceous Mammal from Mongolia: Ravjaa ishiii

A newly described Cretaceous mammal adds to the growing evidence that mammals were diversifying alongside dinosaurs. Fossil jaw and tooth anatomy reveals unique traits used to identify the species and understand its lifestyle. Small mammals occupied many ecological roles in the Mesozoic; not just “tiny insect eaters,” but diverse animals with varied diets and behaviors. These fossils help fill in the gaps of mammal evolution long before the Age of Mammals took off after the dinosaurs.

Student-Found “Razor-Toothed” Jurassic Mammal Jaw from Dorset

A student discovered a tiny fossil jaw that represents a previously unknown Jurassic mammal. Tooth shape and jaw anatomy were distinct enough to identify a new species and interpret its diet. Mammals were diversifying into specialized forms earlier than we once assumed, even during dinosaur-dominated ecosystems. Unfortunately, small mammals often get overlooked in public paleontology, but they’re extremely important for understanding how modern mammal diversity evolved.

Ancient Bee Nests Found Inside Bone Cavities

Researchers documented fossil evidence of bees nesting inside bone cavities, including vertebrae and teeth, preserved as trace fossils. The nests were preserved as structures inside bones. Insects have long exploited natural cavities for nesting, and caves can preserve delicate traces of behavior that would otherwise disappear.

A 407-Million-Year-Old Fossil Shows Early Plant–Fungus Partnerships

Devonian plant fossils preserved evidence of fungi living in and alongside plants. Fossils preserved internal fungal structures in three dimensions, which could be studied in detail. Mycorrhizal relationships (the partnerships between plants and fungi that help plants acquire nutrients) may have been shaping ecosystems very early in terrestrial history. This discovery supports the idea that plants didn’t conquer land alone; they did it with fungi, changing Earth’s landscapes in a big way.