A Dinosaur's Journey: What happens to the bones we find and why can't you keep them?

One of the most common questions we get asked about our field work is what happens to the fossils that we dig up. These fossils go on a long journey from their resting place in the rocks of Montana to their final destination in the collections of a natural history museum. Paleontology field work is more than just treasure hunting, and the fossils we excavate every summer are essential scientific data that helps us learn about how dinosaurs and other extinct organisms lived and died. The process that a dinosaur goes through to become a fossil is a fascinating tale in itself, but today we will focus on what happens millions of years later after a lucky human discovers its bones.

Our fossilized dinosaur skeleton begins its journey in the rocks of the Jurassic Morrison Formation in the Bighorn Basin of Montana. The Elevation Science crew sends a group out into the basin to go prospecting, and one lucky fossil hunter finds a small chunk of bone, called float, on the ground. Next to this piece of bone is another, and as the crew follows the pieces of bones like breadcrumbs we find larger bones in situ, still encased in rocky matrix and covered in dirt. We then spend our field season excavating the skeleton, digging in the dirt, revealing more bones, and making jackets to protect the fossils on the next step of their journey. We make maps of the site using high-tech drones or trusty pencils and paper and take meticulous notes on our new discovery. Many sites take more than one season to excavate, and the Mother’s Day Diplodocus quarry has been worked on for over 20 years!

After our dinosaur skeleton has been encased in plaster jackets and removed from its rocky grave, it is taken back to our camp and loaded onto a truck at the end of the field season. This truck carrying tons of dinosaur bones makes its way across the country all the way to the Elevation Science lab in the Academy of Natural Sciences in Philadelphia. Here, a team of trained staff, students and volunteers work on cleaning up and reassembling the bones. These fossil preparators cut open the jackets, remove the bones, and work on getting them into a stable condition for storage in their final destination. All the matrix (the rock, dirt, and sediment covering the fossils) is removed, and broken bones must be carefully reassembled using special glues and putty. The process of preparing a single dinosaur skeleton can range from months to years depending on the number of people working on it, the composition of the matrix, and the amount of fossil material that needs to be prepared.

When our dinosaur is all cleaned up, stabilized, and ready to move on to its permanent home, it is taken to the Cincinnati Museum of Natural History and Science. Since our fossils are collected on land under the control of the federal Bureau of Land Management, all the dinosaurs we find must be made available for the public to learn from, so they must end up at a scientific repository like a natural history museum. They will be stored in the museum’s collections under the care of curators and collections managers, where they will be available for researchers to study and contribute to our scientific understanding of these animals and their ecosystems. Our staff and researchers from other institutions have published scientific papers on the fossils from our sites which you can check out on our research page.

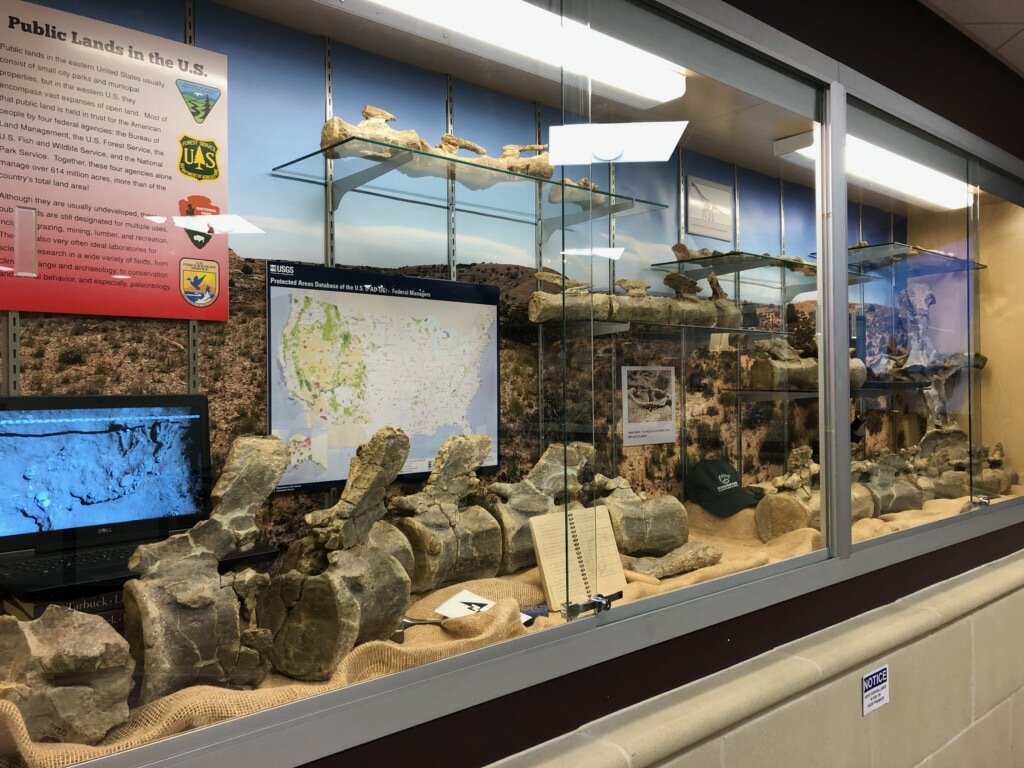

But our fossils don’t always stay in the collections! Education and outreach is one of the core parts of our mission, and putting these fossils on display is a great way to inspire the public, including future scientists. We set up an exhibit of our own in collaboration with Upper Dublin School District in Philadelphia in early 2020 that featured the beautiful vertebrae of our Suuwassea specimen, real field journals, and an immersive 3-D representation of our field sites complete with mapping grids, buckets of plaster, and a water cooler!

One of the other common questions we get asked about our field work is if we can keep a few dinosaur bones for ourselves. Discovering a dinosaur is such an exciting experience, and keeping a little bone may seem like a fun souvenir, but taking dinosaur bones for private collections is both detrimental to science and often illegal. Removal of vertebrate fossils from the Bureau of Land Management property where we work is illegal without a permit, and we have to regularly renew the permits for our excavations. You can read more about paleontology on federal lands here.

If you’re joining us as an expedition crew member this summer, you are allowed to keep some non-vertebrate fossils for personal use, but not for commercial purposes. This means if you find shells from marine invertebrates or pieces of petrified wood that are not of scientific value, you’re welcome to take those home as souvenirs! And you can always come visit us in the lab if you want to see any of the dinosaur bones again, but these fossils can’t go home with you. Even the smallest bone can provide vital scientific data, and it is important that these fossils are properly preserved and made available for the public to enjoy and to learn from. Fossils are an essential resource for revealing the secrets of the history of life on our planet, and it is an honor and a privilege to be a part of their story.